Larissa Luecke

CLST 331 - Dr. Kevin Fisher

University of British Columbia

April 1, 2019

Download PDF

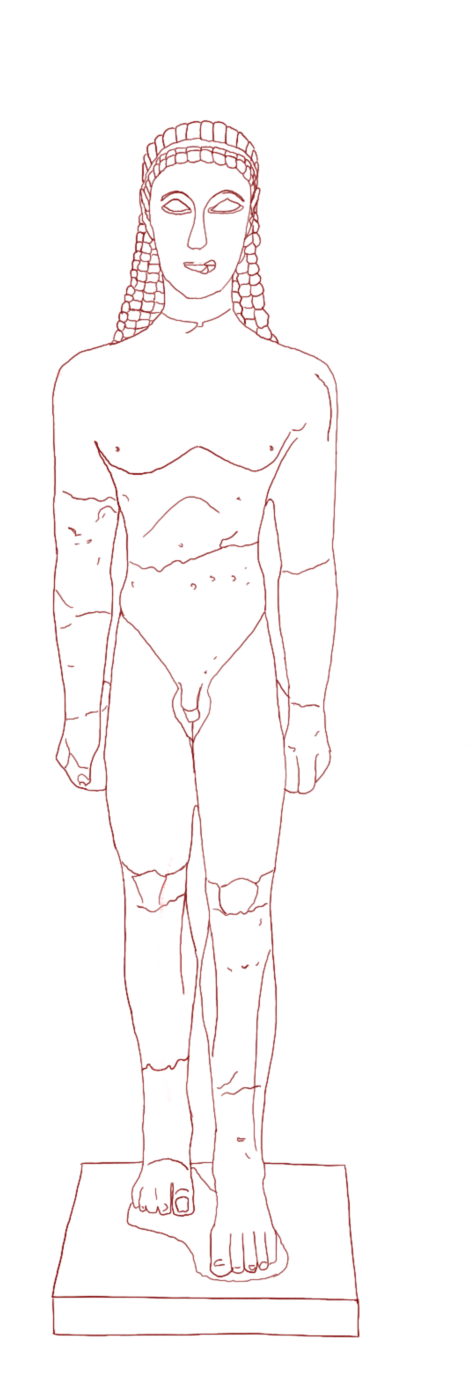

The Archaic period from approximately 660 BCE - 590 BCE encompassed a revival in artistic and scientific reasoning that emerged from a period of disorganization (Levin, 1964, 14). With this revival, the Archaic period can be viewed as the beginning of Greek monumental sculpture (Richter, 1970, 1). Kouros statues (see figure 1), displaying a nude male youth with broad shoulders and a narrow waist (Richter, 1970, 1), have clear stylistic connections to contemporary Egyptian statuary. In the late period of Egypt’s history, Egyptian political revival forced Egypt to return to its classical Old Kingdom era for inspiration to increase nationalism (Levin, 1964, 14), which took the form of sculpture. As it is in the nature of the Egyptian to remember (Levin, 1964, 14), technical tools and artistic concepts such as the 2nd Canon of Proportions, the grid system, and the strong idealized male figure, created once again the Egyptian’s idealized artistic expression (Davis, 1981, 81).

Through external interactions, Greece saw this new Late Egyptian period and subsequently earlier periods of art, such as the monumental statues of Ramesses II (Levin, 1964, 15). Adoption and adaptation of Egyptian ideals of monumentality created the greek version of the ideal individual, the Kouros statue (Davis, 1981, 81). Through the use of historical, social and political context, combined with similarities and differences, a comparison of form between a Kouros statue from Attica and the Old Kingdom statue of Menkaure will be conducted. This paper intends to show how the Greeks created their Kouros statues based off of their social interactions with Late Egyptian culture that stems from Old Kingdom craft specialization. This is supported by a digital comparative analysis using modern technologies that can be found at https://clst331.rissy.de. The use of a visual tool to physically overlap both sculpture’s forms, allows the viewer to grasp a better understanding of the cross cultural exchange between each ideal monumental figure.

Greek

Period: Archaic

Date: ca. 590–580 B.C.

Culture: Greek, Attic

Medium: Marble, Naxian

metmuseum.org

Comparison

Type: Technical Drawing, Procreate

By: L. Luecke, 2019

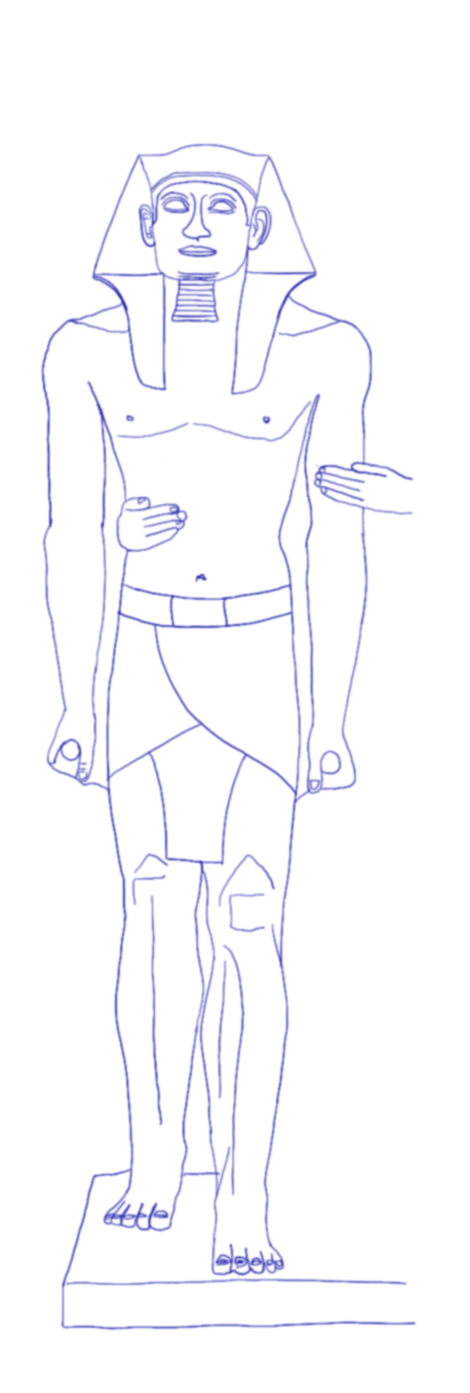

Egyptian

Period: Old Kingdom, Dynasty 4

Date: 2490–2472 B.C.

Culture: Egyptian, Giza

Medium: Greywacke

mfa.org

There are a few explanations as to how the Greeks learned about the Egyptian ways of sculpture specialization. One possibility is that the travelling Greek artists learned the stone carving techniques in Egyptian towns and centers and then developed them further in areas like Samos or Naxos (Ridgway, 1977, 32). Locations such as Memphis, Saqqara, Sais and Naucratis were also ideal for the travelling Greek artist, who would have known what Egyptian art looked like even if they were not totally aware of how the art was made (Davis, 1981, 69).

B. Ridgway also points out that there is textual evidence stating that Samian masters learned their methods from Egyptians and that Samos was an ideal candidate for the Kouros sculpture because it had access to a major sanctuary site and was a crossroad for Egyptian influences (Ridgway, 1977, 32). Also noteworthy is Naxos, as it had an immediate supply of raw materials (such as marble) and had access to the sanctuary at Delos (Ridgway, 1977, 32). These sanctuaries were important areas for Greeks to promote the idealized male figure.

The other way in which Greeks learned their masonry skills was within their extensive settlements throughout Egypt (Davis, 1981, 67). Greek mercenaries were employed by the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II, and therefore intermingled with Egyptians and their children became apprentices in the Egyptian workshops (Davis, 1981, 68). Any Greek students of sculpture would have learned the concept of rhythmos, starting with the Egyptian understanding of form and pattern and increasing its meaning to movement, or a walking pose (Ridgway, 1977, 29). In order to achieve this, learning was done by doing, and the Greeks used the Egyptian 2nd Canon of Proportions and grid system to ensure uniformity from representation to representation (Davis, 1981, 64 & Ridgway, 1977, 29). Using this Canon was crucial to establish standards and order that appealed to the Greek mindset that had stemmed from the Egyptian artistic expression (Davis, 1981, 66).

The Kouros statue has a number of ideas as to its usage. One, as a statue dedicated to the anthroporizing of the God Apollo whose body was seen as a vehicle of the divine (Spivey, 1996, 44). The Greeks honoured the gods using whatever was most beautiful, so things like marble, finesse, precision and skill all added to the monumentality of the piece (Spivey, 1996, 44). This naturalism and idealization of Apollo stemmed from the Egyptian expression of anthropomorphism (Spivey, 1996, 45) and venerating the divine. It has also been suggested that these statues were used a votive offerings in sanctuaries, or even served as markers over graves (Spivey, 1996, 109), which is seen as the most widely accepted suggestion.

The use as grave markers suggests the notion of heroizing (Spivey, 1996, 109). This heroizing connects to the nobility belief of the idealized youthful style, the goal that all Greek men should strive towards (Stewart, 1990, 110). These prestige pieces of the polis elites portrayed people in a “god-like” mode (Stewart, 1990, 110) which Greeks took from the Egyptian mode of representation and Old Kingdom statuary, such as the Statue of Menkaure and his wife (see figure 2). This new means of anatomical display and experimentation of form (Stewart, 1990, 109) allowed the Kouros to become “Badges of Greekness” (Spivey, 1996, 103). This new form of statuary could not have existed without the peer polity interaction (Spivey, 1996, 100) between Egypt and its long standing artistic traditions from the Old Kingdom. The Greek ingenuity of adoption and adaptation aided these grave markers to become widely popular.

A large symbolic interaction of this cultural exchange can been seen in the use of nudity. The Kouros sculptures started out with the basic naturalistic features, such as the torso, head, wig/hair, and the walking pose with musculature, as seen on the Egyptian statues like the statue of Menkaure. This nudity was quickly adapted to increase the heroizing effect with militaristic overtones, with what Spivey calls pseudo-armour (Spivey, 1996, 112). Interestingly, Greek armour was possibly developing body armour at the same time and as cross interaction occurred, the anatomical details from armour made their way into the Greek Kouros (Ridgway, 1977, 37). This is a plausible idea because around the 7th c. BCE, Greek travelers were exposed to Egyptian techniques in statuary and armour making, which gives Kouros statues some of their most notable similarities, like nudity and the walking pose (Ridgway, 1977, 38).

This nudity is seen as a costume that males aspired too, a calling to be higher and better than themselves (Spivey, 1996, 112). The nakedness removed the statue from the sphere of the everyday reality (Ridgway, 1977, 77) just as Egyptian gods and their Pharaohs are seen as not of this mundane reality. This creates an eternal youthfulness that Ridgway connects back to the nakedness of Egyptian god Horus as a child and Ka statues, like Mehkuare, that point to representations of the eternal and divine soul (Ridgway, 1977, 54).

Andrew Stewart argues that Kouros statues are mobile and are filled with a secret life (Stewart, 1990. 110). This can be linked directly back to Egyptian ideology stemming from the Old Kingdom, where statues were endowed with the life force of the person they are meant to represent (also known as a Ka statue). Menkaure was a great king and as such a god on earth. His statue was used in funerary contexts to commemorate and heroize his achievements in life as well as in the next. The Greek polis used Kouros statues for marking prestige and social status of the elite members of society, commemorating their achievements in life, such as the athletic Games held each year.

The stance of the “walking pose” has a direct correlation to the walking hieroglyph created by the Egyptians, indicating physical and metaphorical movement (Ridgway, 1977, 27). This one leg forward expresses a release from immobility and implies a potential for further action in the next world (Ridgway, 1977, 27). This adaptation of the physical form of “walking” allowed the Greeks to adjust the weight of the statue’s torso equally, with no support in the back, making it a more natural form (Stewart, 1990, 108).

In order to achieve this naturalistic form the Greeks used the Egyptian’s 2nd Canon of Proportions and grid system. Their adaptation of these tools created what is known as Ordered Movement (Stewart, 1990, 34). This Canon II grid system divided the standing human figure into 21 squares from the feet to the eyes, and the major anatomical points were then located within the grid and intersected lines (Ridgway, 1977, 30). The Greeks then adopted this technical device for structural guidelines for the form, and then adapted it to get a more realistic representation (Weingarten, 2000, 111) using their observations of nature to influence the way musculature is rendered.

This has led scholars to believe that this grid system, whether used by Greeks or Egyptians, was built on a metrological model defined as, “an anthropometric description of the human body, based on the standardization of its natural proportions expression the Egyptain measure of length” (Weingarten, 2000, 104). This suggests a psychologically intense viewing of the human form, which allowed the grid to become the artist’s tool for the modeling of the conceptualization of space (Weingarten, 2000, 111). In using this Canon II the Greeks were able to use visualization and proportional dimensions to achieve the main goal of idealization (Carter & Steinberg, 2010, 110). This allowed different artists to work on same statue and still have it come out accurate (Ridgway, 1966, 68 & Carter & Steinberg, 2010, 124).

A major difference between the Egyptian’s technical method compared to the Greeks is that the Greeks used 1 piece of stone where as the Egyptians used 2 halves (Ridgway, 1966, 68). This technical difference can be seen in the Egyptian torso and how a median line extends from the collarbone to the navel dividing the toros in half, also known as a bipartite pattern (Levin, 1964, 19). Where as the solid piece of stone allowed the Greek to use a triangular form for the torso, enhancing the collarbone or a tripartite pattern (Levin, 1964, 20). The Greeks made their statues fully naked showing a complete idealization of the individual, where as the Egyptians created the ideal aesthetic (Davis, 1981,81) used throughout their entire reign from the Old Kingdom into the Late Period.

This fixed scheme of proportions allows both cultures to represent clarity and order within the context of their interpretation of the ideal (Richter, 1970, 3-4). This can be seen in the use of colour on the Greek statue’s eyes and lips (Richter, 1970, 10). Although Menkhaure’s statue was never painted, the wall reliefs of human representations in the Old Kingdom and statues of the Later Period were. They show a continuity of artistic specialization within the Egyptian culture that the Greeks are clearly utilizing. Also found within Greek sculptural remains are Egyptian points and flat chisel tools for stone carving (Richter, 1970, 10). Again supporting the notion of Greek traders and multicultural children learning from the Egyptian artisans.

The combination of organic, natural forms and a united spatial plane (Richter, 1970, 12) can call the Kouros a Canonical Kouroi (Stewart, 1990, 109) making both varying degrees of a stylistic abstraction of the human body (Stewart, 1990, 109) based on a pragmatic and flexible Canon (Carter & Steinberg, 2010, 125). This uniform progress allowed the Greeks to view the Old Kingdom statues using direct observations of the eyes, mouth, ears, skull, forearms that all had a more flattened and stylized look (Richter, 1970, 3).

All this combined allows for 2 essential observations regarding Greek Kouros and the Egyptian statue of Menkaure: they were renderings based on the observation of nature and the grid was a model for the conceptualization of space. Despite the Greek’s use of the functional forms of the Egyptian decorative, the Greek’s concept of the idealized male figure for elite heroizing, allowed the Kouros to portray the idealized aesthetic in the same way that the Egyptians portrayed their heros/kings, such as Menkhaure.

Through the international interactions, Greece learned the Egyptain techniques and tools, such as the grid and the 2nd Canon of Proportions, to create monumentally and individualistic expressions. These social interactions of Greek traveling artists and intercultural connections allowed the Greeks to create a new mode of expression based off of Egyptian Old Kingdom craft specialization. Both cultures value consistency throughout their search for the ideal aesthetic. A search, that let both cultures, Greeks and Egyptians to interpret their form of the ideal male elite monumental sculpture based on historical, social and political factors as well as similarities between function and form.

Bibliography

Carter, J.B. & Steinberg, L.J. (2010). Kouroi and Statistics. American Journal of Archaeology

(114:1). 103-128. www.jstor.org/stable/20627645

Davis, W. M. (1981). Egypt, Samos and the Archaic Style in Greek Sculpture.

The Journal of

Egyptian Archaeology 67. 61-81. jstor.org/stable/3856603

Levin K. (1964). The Male Figure in Egyptian and Greek Sculpture of the Seventh and Sixth

Centuries BCE. American Journal of Archaeology (68:1). 13-28.

jstor.org/stable/501521

Met Museum. Marbled Statue of a Kouros Youth. [Image].

www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/32.11.1/

Museum Fine Art Boston. King Menkaura (Mycerinus) and Queen. [Image].

www.mfa.org/collections/object/king-menkaura-mycerinus-and-queen-230

Richter, M.A. & Richter, I.A. (1970). Kouroi, Archaic Greek Youths. The Study of the

Development of the Kouros Type in Greek Sculpture. Phaidon Publishers Inc.,

New York, NY. 1-7, 10-13, 16, 18.

Ridgeway, B. S. (1966). Greek Kouroi and Egyptian Methods. American Journal of

Archaeology 70. 68-70. repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs/38

Ridgeway, B. S. (1977). The Archaic Style in Greek Sculpture. Princeton University Press,

United Kingdom: Guildford, Surrey. 27, 29, 30-33, 37-38, 53-54, 77.

Spivey, N. (1996). Understanding Greek Sculpture, Ancient Meanings, Modern Readings.

Thames and Hudson, Ltd., New York, NY. 43-48, 100-103, 110-112.

Stewart, A. (1990). Greek Sculpture, an Exploration: Volume 1: Text. Yale University Press &

New Haven & London, UK. 34, 108-110.

Weingarten, J. (2000). Reading the Minoan body: proportions and the Palaikastro Kouros. British School at Athens Studies 6. 103-111. www.jstor.org/stable/40916620